|

Berlin

In the spring of my third year at SCAA I received an exciting letter from the American Friends Service Committee. Would I and my wife be willing to spend the next two years as Quaker International Affairs Representative (QIAR) to both parts of the divided Germany? The Cold War was at its height, and the Communist East German government had erected the notorious Berlin Wall. German Quakers had for some time requested that the AFSC send a QIAR to Germany. QIARS were assigned to trouble spots in different parts of the world to work for peace between hostile parties. At the time there were two other QIARS operating at other trouble spots.

In this case, it would mean shuttling back and forth in Berlin across Check Point Charlie and doing what one could to influence high officials and opinion leaders on both sides to draw back from the threatening confrontation which had made Berlin the focal pont of the Cold War. How could a single Quaker accomplish this? There was no expectation that we would come in there and end the Cold War. But perhaps we could make a difference. There is a popular saying among Quakers: "It is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness."

In all modesty, it was easy to see why they had chosen us. They knew us from our two experiences with international student seminars. Beyond that, we had both lived in Germany and knew the language and culture. If we were to do any entertaining of high German officials, it would be nice to have someone like Peg who had majored in German in college and had taught German at Alfred University. My German was adequate, but hers was much more sophisticated. Her efforts as hostess at the student seminars in Denmark and Austria indicated her considerable ability in working with people of other countries, and her earlier experience in France tutoring a family's children in English and in Italy doing the same while she was working on her dissertation were a rich background for international work. Her activities in Quaker affairs indicated that she was experienced in Quaker ways and energetic in her Quaker beliefs. In these respects my background was analogous, and the fact that I was a Herr Professor was a definite advantage in Germany where the respect for professors was very high.

We both thought that such a task would be a fascinating and worthwhile experience. Peg did not push, but she was quietly favorable toward taking it on. I was, as well, except for a complicating factor. I was now in my third year away from a university faculty position, and even then was beginning to be aware that I needed to find a suitable position in some university. Fortunately, I had produced two full length book manuscripts during those three years. I have already mentioned Social Research Consultation. The other was what turned out to be my magnum opus, The Community in America. Those were stars in my crown as I sought a suitable advanced position, and I was already making some overtures. Yet there was still not anything sufficiently solid and to my liking. Two more years away from academia might decrease my prospects of a suitable location. (There was also the limitation, based on our current experience, that I would want to locate somewhere where we could live in an essentially rural setting. That was fine with me, but it limited the area of suitable prospects.)

I was therefore somewhat trepidatious about taking on this otherwise exciting task in Germany. It was a risk that Peg and I talked over, and I think her willingness to take it and put up with what might come or not come afterward tipped the balance. So, we went for it!

It was not easy. We had to break up housekeeping, put our furniture in storage, and work out suitable financial arrangements with the AFSC. We would not be on salary, but they would cover family expenses. With two children in college, storing the furniture, etc., etc., there was considerable back and forth in which Peg took a very strong position regarding finances, for which I am grateful. I was more prone to compromise at our own expense, which as things turned out would have set us back considerably. Peg didn't want us to make any money during these two years, but she didn't want us to lose any, either.

So, in the late spring of 1962, we were off to Berlin. There had been some gaffs by the AFSC. They failed to let the German Quakers know we were coming, and they failed to send us the appropriated money for our upkeep. Fortunately, our own available funds tided us over. We stayed overnight in the hotel room they had reserved for us, but it was so expensive that we sought a more modest pension. The room was fairly comfortable, but we soon found out that the pension was located in the most well-known prostitution block in all of Berlin. In a short time we rented an apartment in a good district and got out of there.

On the first Sunday in Berlin, we went through Check Point Charlie and on to the very small Quaker Meeting in East Berlin. After the worship meeting we introduced ourselves and I said we had met in Heidelberg and had spent a later year in Stuttgart, where I was doing a social science research project. This was all in German, of course. The term I used to convey that research was eine sozialwissenschaftliche Versuchung. I noticed no particular response to this statement. Later, when we were eating lunch in a restaurant in the bombed out section of the city, I asked Peg nervously, "When I talked about my project in Stuttgart, did I say Versuchung instead of Untersuchung?" "Yes," she nodded with a slight smile. So what I had said I had done in Stuttgart was to make "a social scientific temptation." No-one in the meeting had batted an eye!

Peg bore the brunt of setting up housekeeping and getting us organized domestically. She also chased around looking for a suitable school for Robin and eventually settled on the Gertraudenschule, where Robin spent two highly rewarding educational years.

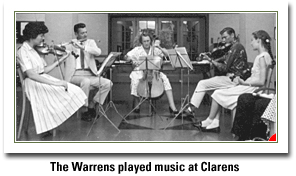

Early on, we looked up a German family who had participated in an AFSC-George School exchange program by harboring the daughter of some of our Alfred friends. By phone, they invited us to dinner, or rather, Abendbrot. Having heard that they were musical, we took our instruments along, Peg with her cello, Robin with her violin, and I with flute and viola. To our delight, the father played violin, the wife played piano consummately, and gave piano lessons. One daughter played violin and another played cello. They also had friends who played various string instruments. We thus began a series of Sunday afternoon/evening get-togethers with a group of about a dozen musicians. These sessions were among the most enjoyable experiences of our lives. In addition, by coincidence, the father taught science in the very school which Peg had selected for Robin to attend. Peg and Robin during this time took lessons on their respective instruments. I needed lessons at least as much as they did, but it would have been a little too much of a drain on my time.

During our two years in Berlin, Ursula and David came over in the summer, and among other things we all attended the Conference of European Friends in Birmingham, England, and at one point entertained the assemblage with a musical quintet

During our two years in Berlin, Ursula and David came over in the summer, and among other things we all attended the Conference of European Friends in Birmingham, England, and at one point entertained the assemblage with a musical quintet

Peg joined in some of the many interviews I conducted in Germany, but I did most of them alone. I will not describe here my interesting experiences with high officials on both sides of the Berlin Wall and in Bonn, West Germany. They are recounted in Mike Yarrow's Quaker Experience in International Conciliation and in my book, A Range of Peaks.

Peg and I were soon invited to a cocktail party given by the correspondent of United Press. Most of those present were diplomats, including the Third Secretary of the Soviet Embassy. I talked with him and took his card and soon visited him at the Soviet Embassy in East  Berlin. There grew up a tenuous friendly relationship, and after talking it over with Peg (who did all the hostessing in those two years) I invited him and his wife and six-year-old daughter for dinner and the evening at our house. The house was a large one with a nice well-kept yard with fruit trees in a fine residential section. It served well for the entertaining that was part of our task. Herr Kolnikov was more fluent in English than in German, so the evening was auf Englisch. Robin was thirteen. During the evening, she took her guitar and played and sang several folk songs in German, English, and French, and a popular Italian song, Non ho l'etá and one in Russian. We asked Herr Kolnikov if he could get Robin's Russian words plainly, and he answered with his thick Russian accent, "Of course!" Ever since then, that "Of course!" has been a by-word in our family. They then had their six-year-old daughter play for us a little ditty on the piano, which she did very well.

Berlin. There grew up a tenuous friendly relationship, and after talking it over with Peg (who did all the hostessing in those two years) I invited him and his wife and six-year-old daughter for dinner and the evening at our house. The house was a large one with a nice well-kept yard with fruit trees in a fine residential section. It served well for the entertaining that was part of our task. Herr Kolnikov was more fluent in English than in German, so the evening was auf Englisch. Robin was thirteen. During the evening, she took her guitar and played and sang several folk songs in German, English, and French, and a popular Italian song, Non ho l'etá and one in Russian. We asked Herr Kolnikov if he could get Robin's Russian words plainly, and he answered with his thick Russian accent, "Of course!" Ever since then, that "Of course!" has been a by-word in our family. They then had their six-year-old daughter play for us a little ditty on the piano, which she did very well.

So far as I know, this occasion was unprecedented, for Soviet officials rarely came to West Berlin, and then only on official diplomatic or military business. I must confess that the thought entered my mind that Herr Kolnikov might simply have been designated by the Soviet Embassy to keep track of this Quaker peacemaker rattling around like a loose cannon in East and West Berlin talking with high officials on both sides of the Wall in these highly tense times. (I also entertained the possibility that our phone might be tapped - by East Germans, West Germans, Russians, or the CIA - but the thought did not bother me, for I was operating on a basic principle: I would never say anything on one side of the Berlin Wall that I was not willing to stand by on the other side.)

Peg arranged for a number of evenings with diplomatic personnel from England, France, East and West Germany, and the U.S. These, too, were unprecedented affairs. It even got to the point that two Russians from their Embassy came and insisted on bringing special crab meat and on making the salad. This was at the high point of the Soviet/Western confrontation, and Berlin was its focal point. Of course, (there I go -- "Of course!") Peg was at the center of these evening supper gatherings and saw that the whole thing went smoothly, both socially and logistically.

In those days we were fond of Manhattans at our cocktail hour. The sweet Vermouth was easy to acquire, but the whiskey was harder. Germans don't go in for whiskey (having their own types of poison) and they don't go in for Manhattans. So, all we could find was a German-made Scotch, which would have curled the hair of any Scottsman. From the local store where she did the shopping, Peg had a big order of food delivered, including two bottles of sweet Vermouth. The delivery man, just making conversation, asked her if we drank the Vermouth straight or mixed it with water to make it milder. Peg nearly floored him with her spontaneous reply: "Oh no! We mix it with whiskey."

In those days we were fond of Manhattans at our cocktail hour. The sweet Vermouth was easy to acquire, but the whiskey was harder. Germans don't go in for whiskey (having their own types of poison) and they don't go in for Manhattans. So, all we could find was a German-made Scotch, which would have curled the hair of any Scottsman. From the local store where she did the shopping, Peg had a big order of food delivered, including two bottles of sweet Vermouth. The delivery man, just making conversation, asked her if we drank the Vermouth straight or mixed it with water to make it milder. Peg nearly floored him with her spontaneous reply: "Oh no! We mix it with whiskey."

It was at about this time that President Kennedy was assassinated. I, Roland, had just flown back to Berlin from Bonn. I hailed a taxi to be taken home. The cab's radio was on. With an awed expression, the cab driver said: "President Kennedy has just been shot." We listened intently as he drove me through the streets to our residence on Patschkauerweg. As we drove along, the announcer reported that Kennedy had now died. He let me off, and I went in and Peg and I commiserated over the news.

Peg had just returned from a rehearsal of the orchestra of the Free University of West Berlin. They had been rehearsing Beethoven's Sixth Symphony, when someone rushed in and announced the sad news of Kennedy's death. The orchestra's conductor, a widely famed musician, put down his baton and stood silently in shock and grief. No one moved in the orchestra.

Finally, the conductor said a few quiet words of grief and said that it would be fitting to call off the rest of the rehearsal, but the imminent concert made it necessary that they continue rehearsing.

They played a few measures, and Peg felt that she could not continue. She quietly took the music from her stand and took her cello and bow to the back of the room to pack them.

As she quietly left the rehearsal room, the conductor once more put down his baton and solemnly announced:

"That will be all for tonight."

Peg's hostessing duties seldom ceased. We were invited to take charge of an AFSC international diplomats conference in Clarens, on Lake Geneva, Switzerland. There Peg was hostess again, with much the same duties as in the international student seminars. Besides the "mothering" activity when needed, and overseeing meals and accommodations, she took some of the young diplomats on excursions. One was to the famous cheese factory in Gruyęre, and another was to a likewise deservedly famous Nestlé chocolate factory. She also had to see that the guest speakers -- well-known professors from Yugoslavia, Poland and the Soviet Union -- were contented and well cared for. She also helped an international group of children of diplomats put on a self-written skit.

|  |

I now made a trip to the U.S. both to give a talk about our work at the AFSC annual meeting and to act as rapporteur at an international social work conference which was held at Brandeis University. This gave me a chance to size up Brandeis, and gave the faculty and administration there a chance to size me up, as well. As a result, I joined the Brandeis faculty when we returned to the U.S.

Before I left on that trip, Peg and I had been invited by two Romanian diplomats to dinner and the evening at a Hungarian restaurant in East Berlin. The day before that engagement they telephoned and asked for me. Peg responded that I was abroad, and they said with alarm that they thought we all had a dinner engagement for the following evening. Peg told them not to worry. I would arrive at le Havre, France, and had flight arrangements direct to Berlin, and we would both be there on the next evening at the agreed time of 8:00 PM.

The evening was most enjoyable, but in the midst of it I got another one of those Walter Mitty feelings. Here were Peg and I in a Hungarian restaurant in East Berlin, conversing in German with two Romanian diplomats, while to top it all off, the restaurant band was playing "When the Saints Come Marching In!"

Continue with Warsaw

Return to My Peg |