|

U. S. Navy

They finally got to Cambridge and Peg began living in that attic apartment, which was very warm and rather confined, and involved climbing stairs to get up there. Peg held out admirably during this hard time, and we were both glad we could be together. I could visit for an hour at supper every evening and had liberty from Saturday afternoon until Sunday night. After a month or two, the second-floor apartment below us became available. When we moved down into it, our telephone remained on the third floor. We were not particularly affluent at the time, and hated to pay to have it reconnected on the second floor. So we decided to lower the phone through the dumbwaiter to the second floor, having to detach it upstairs before we began.,We were somewhat nervous and apprehensive about it, and as luck would have it, no sooner did we get it reconnected downstairs than the phone rang. We both looked at each other apprehensively, fearing that the phone company was calling to scold us about our misdeed. Luckily, it was only a simple, routine call from a friend. But we never forgot the experience of sneaking the phone down the dumbwaiter to avoid the charges to reconnect it. The second floor apartment was a lot cooler, but it was still quite a harrowing time for Peg in her late pregnancy. She gave birth to David at the Chelsea Naval Hospital on July 28, 1943. After completing the several months training in naval communications, I was ordered to the naval base at Norfolk, Virginia, to report for duty and await further orders. While there, I served communications watches at the base. Soon, Peg came down to Norfolk to be with me in an even smaller apartment. She was there only a day or so when I received orders to report immediately for duty on the U.S. Block Island there in Norfolk, a small aircraft carrier. This news was disconcerting not only that this meant goodbye and back to Alfred for Peg, but also because at that time we learned of the Liscome Bay, a small aircraft carrier that took a torpedo hit in the Pacific and went down in sixty seconds with all aboard. I was on the Block Island from December, 1943 to May 29, 1944, when she took three torpedoes and fortunately stayed afloat for an hour and a half. Apparently, some of our friends in Alfred learned of the sinking before Peg did. Peg was moderately surprised as one friend or another came by the house and paid her a visit. As I recall, it was only when Peg received my telegram from Casablanca that she knew that my ship was torpedoed but I was safe. I came home in June on thirty days survivors leave and then received orders to report in ten days at Bremerton Navy Yard, in Washington State, where a new small carrier was under construction, to be named the Block Island after the sunken ship which had such a good war record against German submarines in the Atlantic. It was the only major ship I know of that was named after its sunken predecessor and was staffed with the crew that had survived the first disaster. I had to travel to Washington, DC to receive my new orders. Immediately after getting them, I telephoned Peg and we decided that she and the children would accompany me to the West coast and we would be together there until the new Block Island sailed away. I would take the night train back to Hornell (near Alfred) and she would meet the train there, with the children and our luggage, already to take off for the West coast. With twenty-four hours notice she closed up the house, told our neighbors, and loaded up the car with as much as it would possibly carry, including a crib, radio-phono set, suit cases with clothes, crib and mattress, folding stroller, odds and ends, and two old tires on the roof of the car. She had also packed in baby food, bottles, a thermos jug, potty and potty seat, all these to be immediately accessible. Leveling all of this in the back seat area, she spread sheets and blankets over everything, thus making a roomy area where the children could sit, play, or nap. This was another example of Peg's ingenuity and willingness to take on hard jobs. So loaded, including Ursula (nearly three years old) and David, still a yearling, we set off from Hornell in the old 1936 Plymouth which we had bought second hand when we were married in 1938. I always thought that Peg would have made an excellent frontier wife. She had not only patience and a keen practical mind, but she was ready for anything which fate demanded of her, and she suffered the hard times - and there were many - without complaint. Her quick mind enabled her to think of ways to overcome or minimize problems as well as inventing ways to keep the children happy and life interesting for me. Just consider our trip across the country. We were issued enough gasoline coupons to be able to purchase the rationed gasoline as we drove along. Our tires were shot but we were able to get chits to purchase retreads. Consider the back seat of this seven-year-old five passenger car: It was loaded with all the clothes cooking equipment, towels, bedding, etc., etc. that we could get in it. Over everything Peg spread some blankets and quilts, on which the two children rode during the trip which lasted six or seven days, as I recall. We got as far as Ohio when the tread came off one of the tires. Luckily, we had our old, worn-out tires on the roof rack, and we replaced the useless tire with one of the old tires. I believe it was three retreads in all that lost their treads before we got to Bremerton. On the way, Ursula developed a high temperature which needed attention. We stopped at some doctor's somewhere along the way. The trip was a trying one for Peg, who had to fuss with the two young children, along with everything else.

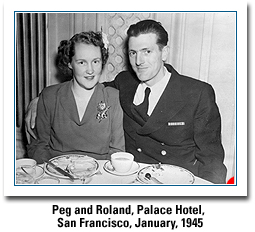

Yes, Peg packed up the children and our car full of household things and struck out for San Diego. On the way, they stayed overnight with the wife of a fellow officer who lived there. When they got to San Diego, Peg rented a small suite of rooms with kitchen. I was able to visit daily, but soon my ship was to be off on a more extended shakedown cruise, so Peg started the long trip home to Alfred. There she was with a car now eight years old with risky tires, full of all our stuff and two young children, heading out on the three thousand mile trip to Alfred. At that time, I had it much easier than she did. The ship was not yet in a combat zone. As visual signal officer, I was in charge of the signal crew who managed the flag hoist commands to our destroyers, as well as the numerous flashing light messages to or from them, given in Morse code. I had three square meals a day and a comfortable bunk to sleep in. I didn't have to worry about two young children getting restless during the long days driving, or figuring out how to get them to the toilet somewhere several times a day, or stopping for eating, or seeking out a suitable motel for overnight; or worrying to death if the car's motor sputtered in some desolate stretch of desert or mountains. Peg had her difficulties getting back to Alfred with the children. In her letters to me (written at length and almost daily throughout the Pacific war), she described some of the harrowing experiences. Those letters are still extant, for she kept carbon copies and I later had them bound. Seeking places to stay overnight and getting supper somehow and putting the children to bed after a long day's driving was always a wearying experience, and of course this was January, the middle of winter. One of her troublesome experiences was at a seedy motel, the only one she could find after they had been looking for miles. She didn't like the looks of the proprietor, and the whole thing was shoddy. It turned out to be one of those shady outfits that rented rooms hour by hour for couples having their clandestine liaisons, and the whole experience was so mortifying that she had to pack up the children and drive on miles through the night to another place. Days later, as Peg drove through Ohio and parts of Pennsylvania, there was a blizzard which left snow banks several feet high along the road, and still snowing. She finally made it to Alfred, and set about resting herself and the children - and the faithful old car.

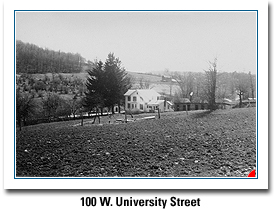

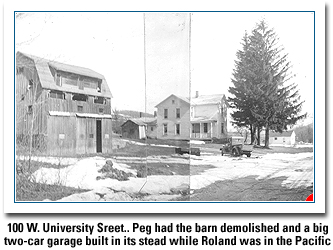

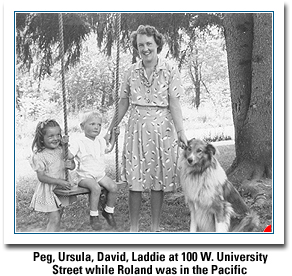

Her letters to me over the next several months were replete with detailed descriptions about getting the house financed and purchased, and then her working herself to a frazzle fixing it up. A prime enterprise was to supervise the demolition of an old decrepit barn on the corner and to build in its stead a roomy two-car garage. Her letters contained a description of her bouts with service men, many of whom we knew personally in this small town, of her many visits back and forth with various faculty couples, of the job she was doing in painting and decorating the rooms, of wily purchases of furniture in second-hand stores, of just what she was doing with the children, and on and on. In the Pacific, whether I was in Ulithi, the Philippines or Okinawa, the waters off Borneo, Guam or Saipan, I could envision just what was going on in our new home and look toward the day when I would be able to join her there.

I happened to be on Saipan when news came of the nuclear bomb and Hiroshima. That was in August, 1945, and I was home in Alfred just before Christmas. That was a happy reunion. We continued working on the house, which was now in good shape, but we had some further projects together. The university administration arranged some ad hoc work for me until the fall, when I resumed my normal teaching duties. Continue with 100 West University Street |